Hasan Korimullah is a 16 year old Rohingya refugee living in Chicago. His tragic experiences of fleeing the genocide in Burma represent what many Rohingya have suffered at the hands of the Burmese government. Resettling in America is a new start for Hasan and presents an opportunity to be part of a new community - a new family, but it may not be enough.

For more information on the Rohingya and on Chicago’s community, please visit the link below.

It Will Be Like Magic - 2018

It's a dark starry night, partially lit with a beautiful half-moon. Hasan picks himself up to accompany his mother on a quick shopping trip for groceries in Fuk fara, a small farming village close to the township of Maungdaw in the Rakhine State of Burma. His mother’s black hair flows long down her back. She's wearing a dark kameez, or tunic, patterned with flowers. Hasan loves his mother dearly; he made sure to always share the candy she gifted him. They walk carefully, Hasan a few strides ahead of his mother - it's not safe these days for the Rohingya. In 1982, the Burmese government enacted the Citizenship Law, recognizing 135 other ethnic groups in Burma – not the Rohingya. This effectively stripped the Rohingya of all basic rights in the country. The domestic conflict between Rohingya Muslims and Buddhist nationalists has been growing and even a short, ten-minute trip to the market could be perilous.

As they walked, seven men with machetes came out of the darkness. Gripping machetes and crazed with bloodlust, they attack his mother from behind. This is not a charged personal vendetta. This is a hate crime fueled by toxic nationalism. She screams to her nine-year-old son, signaling him to run - and Hasan does. He hears the screams of his mother, and looks back to see her lying on the ground, lifeless. He runs as fast as he can back to his village. There is nothing he can do. He does not stop running until he reaches his home. He tells his father what happened. His father, accompanied by a few villagers and Hasan himself, quickly go back to seek the assailants, but who are nowhere to be found. They only find his mother, her flowery kameez stained red. They bring his mother back to their village. He waits. When morning comes, with the help of his village, he buries his mother after a congregational prayer, or janazah.

The Rohingya have lived on the western coast of Burma for centuries, currently known as the Rakhine State. They are physically separated from the rest of the populace by the Arakan Mountains. They speak Rohingya, a dialect unspoken in the surrounding regions. To the Buddhist-Nationalist Government, they don’t belong.

The military government that has ruled Burma since the 1980s mixed nationalism with Theravada Buddhism as a means to fortify its claim to power. It disputes the authenticity of the Rohingya's historical settlement in Burma, and seeks to homogenize Burma into an all Buddhist state. It incensed pogroms against the Rohingya as a means to drive them out of Burma.

A few months pass since the tragic murder of Hasan's mother. Hasan is left with agaping hole in his heart. Life proceeds with caution. Hasan and his family hear of riots in neighboring villages, people fleeing, homes being burned –they pray that God will spare them – their home. It's a spacious bungalow, made with bamboo and wood, a roof made out of leaves and a mango tree towering above. A river flows behind his home where Hasan catches fish - his mother and sisters had taught him how to cook fish. His village is clean, representative of people who care for their land. Mango and coconut trees sway in the cool breeze. There is a small field nearby where Hasan and the village children play soccer there with a makeshift ball.

A Rohingya home burns during riots in the Arakan State of Burma.

*Cellphone images from surviving Rohingya refugees.

(not an image of Hasan’s home)

Hasan is visiting his aunt’s home when he hears the growing, riotous horde of Buddhist nationalists. With them is the Burmese military. There is no time to gather his things. 'My family, where is my family?' he thinks. He desperately searches his village for them but they are nowhere to be seen. The barbaric mob has started to burn his village, slaying villagers and burning infants alive. If he stays, he will die. He has no choice but to join others and again run for his life. He looks back at his house engulfed in flames. He has lost everything: his mother, father, five sisters, younger brother, his village, his home – his hope.

After a few days of trekking through the jungles Hasan and those left from his village reach the sea. He cannot go back, and the sea presents his only option for survival. Hasan joins other Rohingya on boats. He has no idea where it is headed. He is scared; he has never ventured out into the sea before. It’s overcrowded—upwards of 200 people are on board—not all of them alive. It’s a long fishing boat The smells are unbearable. He cannot stomach it, but that does not matter. There is no food and hardly any water. After 15 days crossing the Andaman Sea, the boat, powered by a small motor, reaches Malaysia.

Not long after Hasan's arrival, he his detained and sent to a detention center reserved for incoming refugees. Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya have fled Burma to neighboring countries: Bangladesh, Thailand, Malaysia. Many died at sea. It's a perilous journey, fleeing death only to be met by a unforgiving sea that is riddled with pirates, and later being arrested upon arrival. But Hasan survived.

The detention camps employ translators provided by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. After eight months of being detained, Hasan is taken to a United Nations office to be interviewed by Yusuf Shukor.

"Where is your family?" Yusuf asks. "Where are your parents?"

"They are all dead," Hasan answers hopelessly, assuming that his family has most certainly perished. He

begins to share his story.

Yusuf is moved to tears and tells Hasan to not worry, "I'll get you out of here soon."

Yusuf is also Rohingya. He was born in Malaysia after his parents escaped Burma some 20 years ago. He shares Hasan's story with his parents, who immediately empathize with Hasan. Yusuf and his family are close to receiving immigration visas to come to America, but decide they won't go until Hasan is released and receives his own visa. Yusuf pleads with his superiors to let his family adopt Hasan and to expedite his release. When Hasan learns of this, he is cautious. He's heard rumors around the detention center of children being taken away by families who are later enslaved or sold into human trafficking. Thankfully however, the Shukors open their home to Hasan and he is released a few days later.

Hasan is anxious to meet this new family. As he enters their home, he sees a mother watching television, children playing around the house, and the older children on their phones. This is all new to him. His version of television was made of mud which he used to make with his friends back in Burma. He would carve out the front 'screen' and the back, and would sing karaoke, idolizing famous singers, while his friends watched. His favorite toy as a child was an old toy telephone that would play tunes when its buttons were pressed. Sometimes he would go fishing in the nearby rivers or play 'ding dong ditch' with the village youngsters. He misses playing his homemade guitar (or 'geetar' as he calls it). But all of that is gone now. This new family is a sign of hope, and he embraces it, he embraces his new mother as she tearfully rushes towards him saying, 'you are our son now.'

After four years, Hasan finally receives his visa and the Shukor family immigrate with him to America, and find themselves in the large bustling city of Chicago. They resettle in Little India, an area in northern Chicago known for its South Asian cultural heritage. Little India is centered around a part of W. Devon Ave, a long and busy street lined with various South Asian restaurants and markets selling fresh produce. Countless cellphone repair shops are hard to miss with their flashing neon signs. There are more familiar-looking faces here. Smells of rich curry and sweet desserts fill the air. The honks of impatient uncles on their way to Friday prayer and the sound of people screaming into their phones talking to their distant relatives seem to be the only thing you can hear. This is Hasan's chance to begin a new life, one without the threat of imminent death or restrictions of basic rights. He can go to school, play soccer, and even go to the movies.

He begins school at the 6th grade level, but feels worlds away from his fellow students. He is the only Rohingya and hardly speaks any English. He is experienced in all the wrong things and has trouble relating to his fellow students. While other students daydream, he has vivid flashbacks of his village, his mother, his people. While his days are riddled with horrific memories, his nights are often haunted by nightmares, waking up in sweats, unable to go back to sleep. It is 2012 and the Rohingya crisis is only getting worse.

The Rohingya are relatively new immigrants in the U.S. The immigration system was not prepared to handle such a large influx of refugees. As such, no one in the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services speaks Rohingya. For the most part the Rohingya are unlearned and are nescient of the public system. Simple tasks like applying for a driver’s license or a social security card are difficult because of their language barrier.

Another four years later, Chicago's Rohingya community is blessed to open a culture center and a masjid (mosque) thanks to the efforts of Nasir Zakaria, the director of the RCC and a refugee himself. The Rohingya Culture Center and the adjacent Al-Falah Masjid, the first Rohingya masjid in the U.S., become the center of the Rohingya community, providing a communal place for Rohingya to be amongst their own, to learn, worship, and preserve their culture.

Hasan sees the RCC as an opportunity to bring back something he had lost - soccer. With the help of Nasir and a few others, Hasan starts a youth soccer league. It’s something to take his mind off of his looming past.

It is now summer before Hasan's sophomore year at Sullivan High School. On paper he is 16, but he is really 18. He is the captain of his soccer team, has a girlfriend, and occasionally works odd jobs like painting and construction to earn an allowance. Yusuf and his new wife, Zubedah, are expecting a child. It is also Ramadan, a month where Muslims all over the world fast from dawn to dusk for 30 days. It's a time for spiritual rebirth and prayer. He is seemingly happy - having everything he physically needs and most of everything he wants, except one thing - his family. He tries not to think about it too much, but when he does, he tells himself that maybe they are still alive somewhere. At this point, close to a million Rohingya refugees have been forcefully pushed out of Burma, many of whom have fled to Bangladesh and live in refugee camps. This is where Hasan believes his family may be, but he cannot be certain.

The month of Ramadan brings about weekly community dinners. Hasan volunteers his time to help serve food to his community. He feels an urge to give back and help his community even though he has lost everything he holds dear. As Eid (the ending celebration of Ramadan) approaches, the community and Hasan's new family prepare for celebrations. On Eid morning, Hasan picks out his best kameez to wear to morning prayer. No more fasting after this. He can finally drink water during his soccer games.

Eid is the best time of the year for many Muslims around the world. It is a morning of forgiveness, charity, and celebration. Children often receive 'Eid-ee': money from parents and relatives as a type of reward for fasting. Everything is perfect, but Hasan cannot help but be reminded of the Eids he used to spend with his mother and his family. It is a conflicting time for him. He often feels guilt and is overcome by sadness.

"It makes me feel sad, but I don't show anyone my feelings,” Hasan said. I keep them inside - because in this

world no one understands each other's feelings...Sometimes when I remember my family and

my mom, how she died in front of me like that. It drives me crazy and I feel sad. I don't feel

anything good in this world...Why I am not dead yet? If I'm dead it's better than staying in this

world."

It is now November and Chicago has already been swept with icy winds and inches of snow. Hasan is well into his sophomore year. He plans on taking guitar class as an elective. His favorite subjects are math and history. He's started to think about college. He has goals to become a police officer or a caseworker to help refugees like himself. Hasan breaks out his hooded denim jacket - his signature look. The trees have lost most of their leaves. Fewer people are seen walking about W. Devon Ave. The cold air bites, unlike the cool refreshing breeze he remembers from back home.

Before they left Malaysia, the Shukors gave their phone number to various relatives in hopes that one day it would reach Hasan's family. Today is that day. He receives a phone call from a voice he never expected to hear again - his father. His father is alive, as are his five sisters and younger brother. They had escaped and made it to the refugee camps in Bangladesh. Like many Rohingya, they fled to the safety of the jungles. Hasan's family then took a boat to Bangladesh, costing them roughly 45,000 Taka (around $537). Hasan is overwhelmed with happiness, but feels an unwavering sense of helplessness. His father is sick; the conditions in the camps are unbearable.

Bangladesh is already a densely populated, poor nation, and it’s not equipped to handle one million Rohingya refugees. Now that he knows they are alive, it is driving him mad. He wants to help, but does not know how. He is delighted that they are alive, but guilty he his here, with a warm bed and a roof over his head. He wishes he could being them here in an instant. He's split between prioritizing school and working to earn money for his family. His father is sick. The conditions in the camp are deplorable and they need money to survive. His dilemma is made harder by the reality that he cannot see them. Hasan is not even able to contact them. They don’t have their own phone. His weekends are no longer free to play soccer or spend time with friends. He only works, not for allowance, but for his family. He has one goal in mind, to reunite with his family. He can only imagine what it will be like, but he says he knows "it will be like magic."

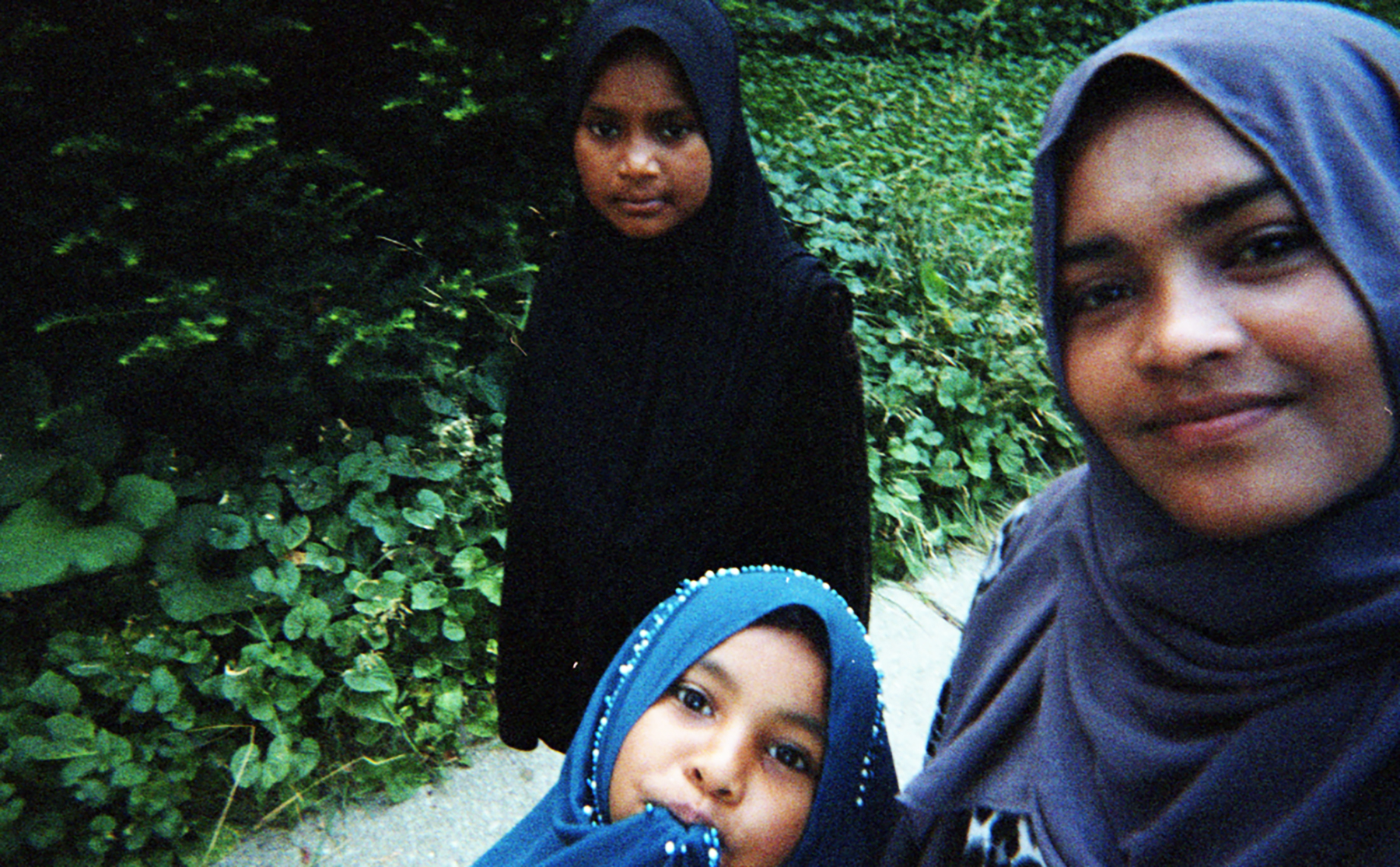

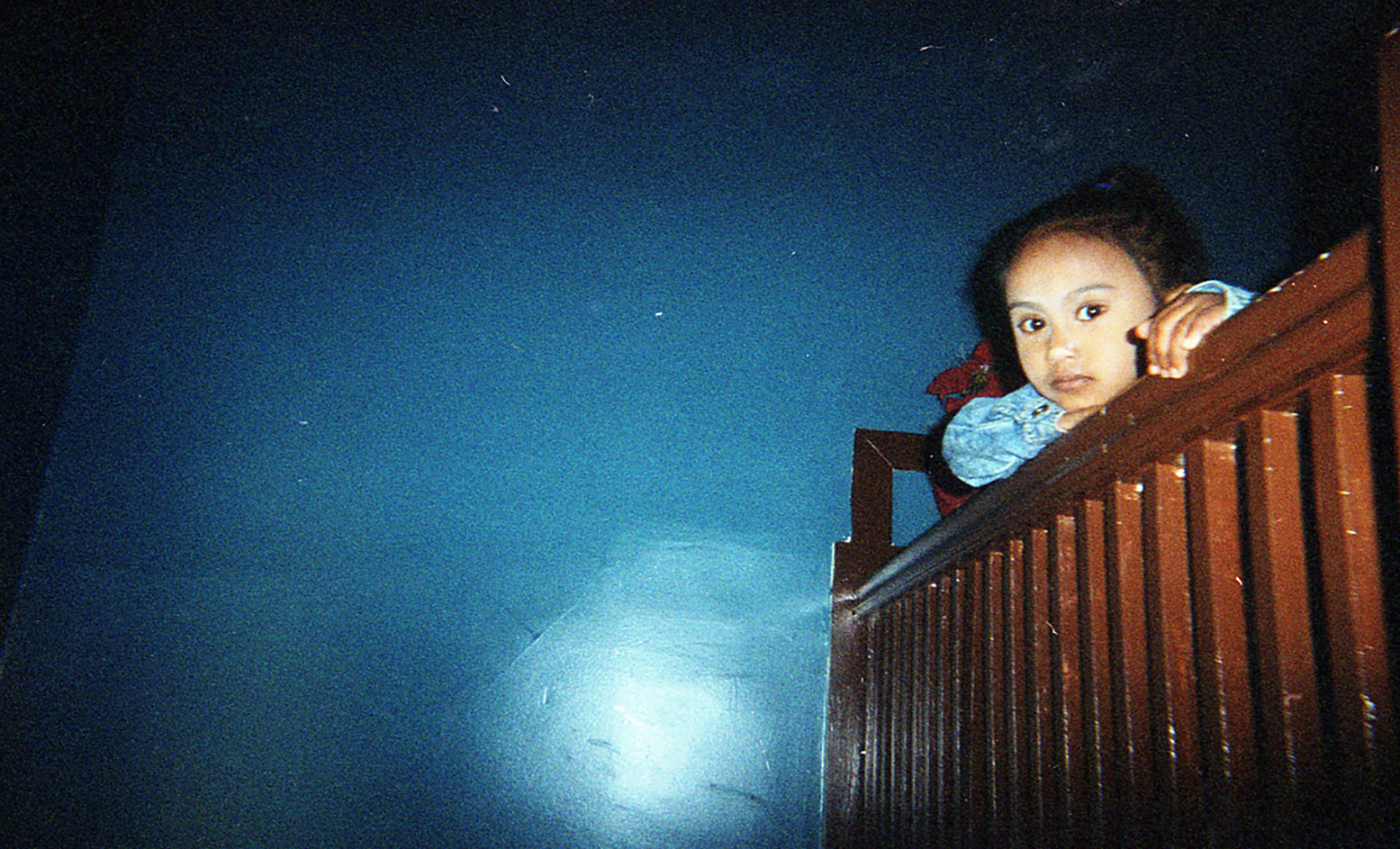

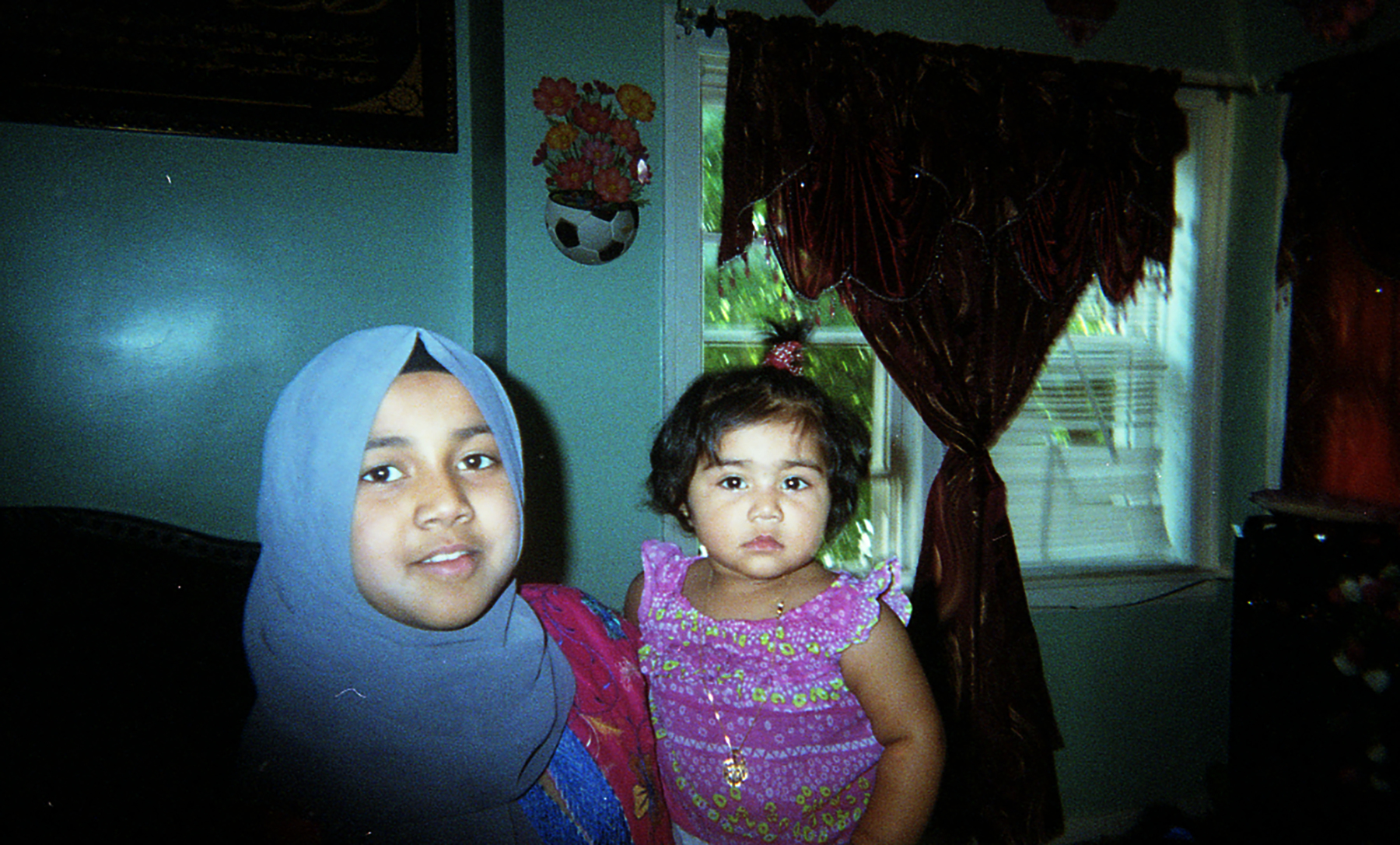

The Shukor Family

The following images were taken on Kodak 35mm disposable cameras by Nurhayati Sultan, a young Rohingya teenager with an interest in photography. These serve as a personal documentation of refugee resettlement from the eyes of a refugee.